Here’s

a challenge for you: name an inventor of an electrical device from before the

Second World War. Who springs to mind?

Thomas Edison? Graham Bell? Maybe William Sturgeon, Samuel Morse or Alessandro

Volta? If you’ve been caught up in the recent surge of near-mythological interest

in Nikola Tesla maybe you think of him? Well here’s one person on the list who you’ve

probably never heard of: Otto Christoph Joseph Gerhardt Ludwig Overbeck.

Overbeck was a man of many interests, and during his life he was a chemist,

inventor, curio-collector, writer, artist and, most notably, a self-proclaimed

discoverer of the key to youth and vitality. The device with which he believed

he had unlocked the secret of a long and healthy life was the Overbeck

Rejuvenator, and armed with a qualified fascination in science and a canny

business mind he marketed one of the most commercially successful

electrotherapy devices ever made.

Born

in 1860, the son of a Vatican priest, Overbeck began his career as a chemist, studying

the subject at University College London until 1881. After becoming a Fellow of

the Chemical Society in 1888 he went on to work at a brewery in Grimsby as

scientific director. Here he was responsible for a few interesting

developments, including an early attempt at making alcohol-free beer and a food

extract product called Carnos which was in fact a forerunner to Marmite. Even at this stage he had begun a rigorous

habit of patenting everything he thought would become a successful invention,

Carnos being his first, which would become a staple of his approach for years

to come. His broad interest in science was evident in his personal library,

which included books not only on chemistry but biology and geology among

numerous other subjects. Such was his enthusiasm that he claimed at one point

to have discovered an element new to science.

Born

in 1860, the son of a Vatican priest, Overbeck began his career as a chemist, studying

the subject at University College London until 1881. After becoming a Fellow of

the Chemical Society in 1888 he went on to work at a brewery in Grimsby as

scientific director. Here he was responsible for a few interesting

developments, including an early attempt at making alcohol-free beer and a food

extract product called Carnos which was in fact a forerunner to Marmite. Even at this stage he had begun a rigorous

habit of patenting everything he thought would become a successful invention,

Carnos being his first, which would become a staple of his approach for years

to come. His broad interest in science was evident in his personal library,

which included books not only on chemistry but biology and geology among

numerous other subjects. Such was his enthusiasm that he claimed at one point

to have discovered an element new to science.

Self-portrait (1902)

In

the following years leading up to the development of his most famous invention,

the Rejuvenator, Overbeck became increasingly interested in the prospect of

restoring youth, seeking a sort of “elixir” with which he could help people

live longer with better health. His artistic side demonstrated this in a poem written

in 1889 called “The Alchemist”…

“Yet one more drop,

& now! What do I see!

The forms of early

youth! Forgotten dreams to me;

Rise with the misty

clouds from age’s wintry rime;

and boyhood’s joy

& health & summer clime

With scent of roses

fills the air!

Old age be-gone!

For eternal youth prepare!”

He was a strong believer in the

idea that electricity was the unifying key to not only life but the entire

universe, and whilst electrotherapy was not a new idea at the time Overbeck was

very keen to demonstrate its benefits to human health. In 1924 he took out a patent for an “Electric

Multiple Body Comb for Use All Over the Body”, the first patent relating to the

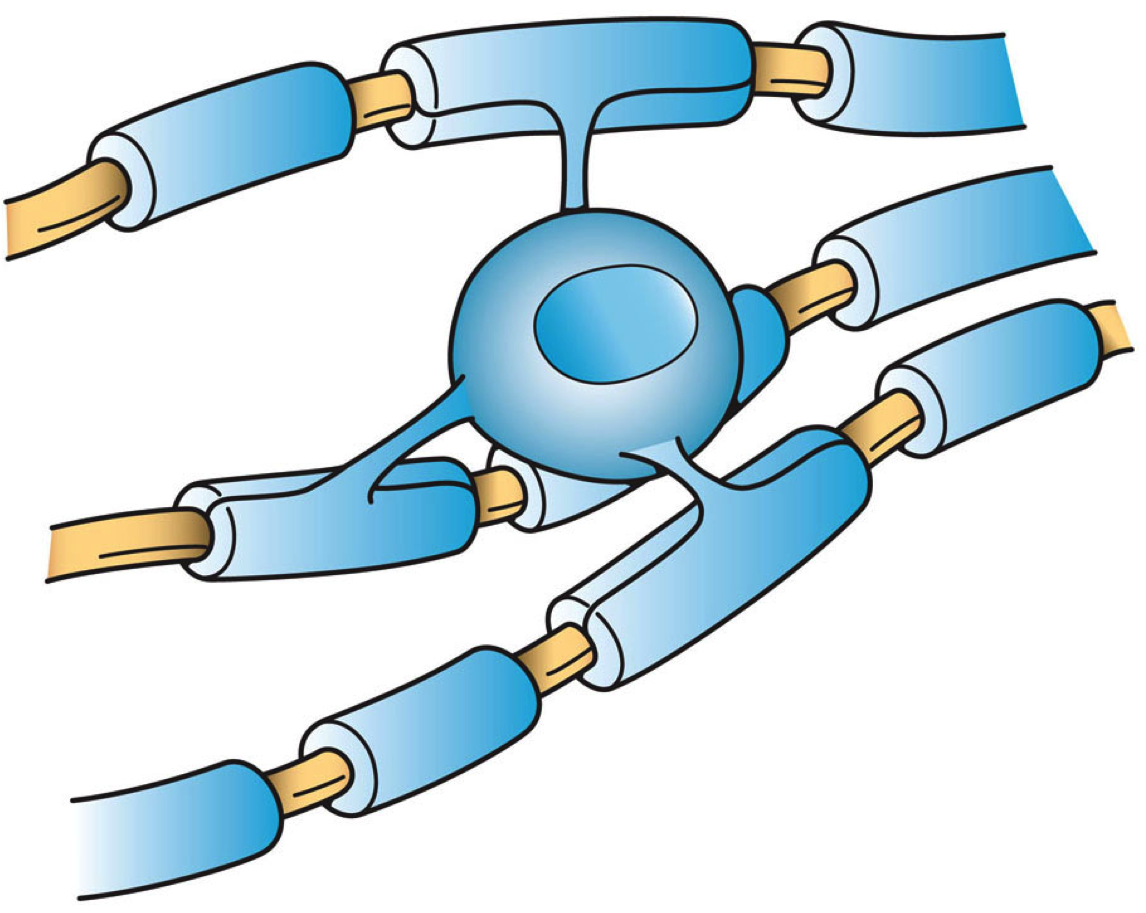

invention of the Overbeck Rejuvenator. The Rejuvenator consisted of insulated

metal combs which, when connected to a battery, applied a weak electrical

current to the area of the body the combs were in brought into contact with. The

patent made no reference to rejuvenating properties, but nevertheless the

product was intensely marketed as a medical miracle. Overbeck frequently backed

up his advertising with testimonials from satisfied customers, with such

whimsical quotes as:

“…elderly members of an east

coast golf club have practised with the rejuvenator, and their handicap has

been halved, and they can play three rounds as against two formerly.”

“I have been using your Rejuvenator for about five

months…and have found it of great benefit. I was suffering from Neuritis, but

[am] pleased to say I have scarcely felt any pain this winter. I have worn

spectacles for 25 years, and now my eyes are wonderfully improved…my hair,

which was white, is being replaced with new dark hair. I think your Rejuvenator

is a wonderful invention.”

In 1925 he published a book on

the subject, “A New Electronic Theory of Life”, in which he presented the

importance of electricity in conventional medicine. He cited numerous eminent

scientists of the time to back up his ideas, but he also frequently referred to

the Rejuvenator itself throughout as a cunning marketing strategy. This was a

rolling theme in the promotion of his device: using his position as a scientist

as a role of authority through which he could persuade people to buy the

Rejuvenator. Overbeck claimed it could treat all kinds of ailments from asthma

to psoriasis, and the BMA (British Medical Association) was becoming

increasingly concerned that the layman would start to ignore conventional

medicine in favour of this “easy fix” which had so far not shown much, if any,

quantifiable medical success. A model of the device was acquired for testing,

and they found that whilst the device was not necessarily dangerous there was

potential for its misuse to cause ulcers in the mouth. More worryingly, there

was good reason to believe that people using this form of alternative treatment

to treat chronic conditions like diabetes would put off seeking established

medical advice until it was too late.

The Overbeck Rejuvenator was sold

across the British Empire and had a number of variants at prices starting at

around 6 guineas. Overbeck even adjusted his advertising campaigns depending on

where it was being sold in order to further publicise it, encouraging users in

the Colonies to write back to him about their experiences. One of the key parts

of the Rejuvenator’s marketing was a focus on its ability to treat certain

conditions that people felt embarrassed to talk about, such as hair loss. So

successful was the device that he was able to buy a house in Salcombe, Devon

(now a National Trust site dedicated to his work and collections), where he was

able to engage in his other passions of curio-collecting, art, music, natural history

and all other manners of hobbies and interests. But soon the Rejuvenator would

begin to lose traction as Overbeck’s advertising strategies came under fire

from the scientific community…

The Overbeck Rejuvenator was sold

across the British Empire and had a number of variants at prices starting at

around 6 guineas. Overbeck even adjusted his advertising campaigns depending on

where it was being sold in order to further publicise it, encouraging users in

the Colonies to write back to him about their experiences. One of the key parts

of the Rejuvenator’s marketing was a focus on its ability to treat certain

conditions that people felt embarrassed to talk about, such as hair loss. So

successful was the device that he was able to buy a house in Salcombe, Devon

(now a National Trust site dedicated to his work and collections), where he was

able to engage in his other passions of curio-collecting, art, music, natural history

and all other manners of hobbies and interests. But soon the Rejuvenator would

begin to lose traction as Overbeck’s advertising strategies came under fire

from the scientific community…

Demonstration of the Rejuvenator

as a treatment for hair loss.

Investigations were mounted by

the BMA in the early 1930s to contact members who had been apparently quoted in

the Rejuvenator’s advertising campaigns in Australia and elsewhere.

Intriguingly many of the responses said that whilst they had bought the

devices, they had not given permission for their opinions (genuine or not) to

be published. Some outright denied any involvement with the company and

demanded an official explanation. A number of attempts were made to ban the Rejuvenator

on both medical and legal grounds, but none seemed to be successful (probably

in part due to the ruthless patenting and numerous user testimonies which

protected the device). Otto Overbeck died in 1937, but the device remained on

the market up until the Second World War, when resources needed to build it

became too difficult to acquire. Amazingly however, over 30 years after he

filed the original patent for the product, in 1955 an order for a new battery

to power an Overbeck Rejuvenator was received by one of his associates.

Whilst the Overbeck Rejuvenator

was not proven to be of any real benefit to health (despite its inventor’s

insistence), it was one of a number of early electrical devices to appear in

British homes and elsewhere which aided the mainstream acceptance of a

relatively new and revolutionary power source. It also provided a valuable

lesson of the power of advertising, especially when coupled with the authority

of science to persuade the public to buy a product. This is a theme that

continues to this day, see how many toothpaste adverts feature an interview

with dentists! Overbeck may have been mistaken in his faith of medicinal electricity,

he may have even known it was of little use and was simply a very good seller

of his contraption, but one thing remains certain: his multi-disciplinary life story

is one of both eccentricity and intrigue.